Frying the Facts: Media Hype and the Cooking Oil Scare

Debunking the media hype blaming seed oils for colon cancer – by diving into the evidence.

Recent headlines have had a lot of people eyeing their frying pans with suspicion. Clickbait titles claimed seed oils like canola and sunflower might be causing colon cancer. Even some of the more reputable publications fell prey to the frenzy.

This came not long after Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced Americans are being unknowingly poisoned by seed oils. He suggested "It’s time to make frying oil tallow again" and cut seed oils subsidies, apparently to make McDonald’s healthy.

Influencers, media outlets, and politicians have all jumped on the bandwagon, spinning tales of toxic oils lurking in our pantries. But is there any truth to these claims? Let’s break it down with some solid science.

TL;DR – Seed oils don’t cause colon cancer

The argument against seed oils is that the linoleic acid they contain increases inflammation, which is linked to cancer. However, a substantial body of evidence exonerates linoleic acid:

A study which followed 2,480 people for 22 years found that those with higher levels of linoleic acid were 43% less likely to die from any cause, and that higher linoleic acid levels were not associated with cancer deaths, meaning they did not increase or decrease cancer mortality risk.1

Another large meta-analysis, which included 68,659 people in 13 different countries who were followed for up to 32 years, found that people with higher levels of linoleic acid had a 7% lower risk of cardiovascular disease and a 22% lower risk of death from cardiovascular events.2

A meta-analysis of 30 different studies, involving 1,377 participants, found that eating more linoleic acid did not change levels of inflammatory markers in the body.3

The study that sparked the recent seed oil hysteria

It started last month when a study by Soundararajan et al. was published in Gut (by the British Medical Journal).4 Researchers analysed tumour samples from 81 colorectal cancer patients, and compared these to biopsies of non-cancerous tissue taken from a nearby site within the same individuals.

This type of research is classified as a ‘hypothesis-generating study’. These studies are designed to gather observations and form initial hypotheses, which can be tested in follow-up experimental studies in order to draw reliable conclusions. In the case of Soundararajan et al.'s study, its observational nature (and the reliance on data from a single point in time) make it impossible to determine how the observations occurred, allowing only for hypothesis generation at this stage.

What did the study show?

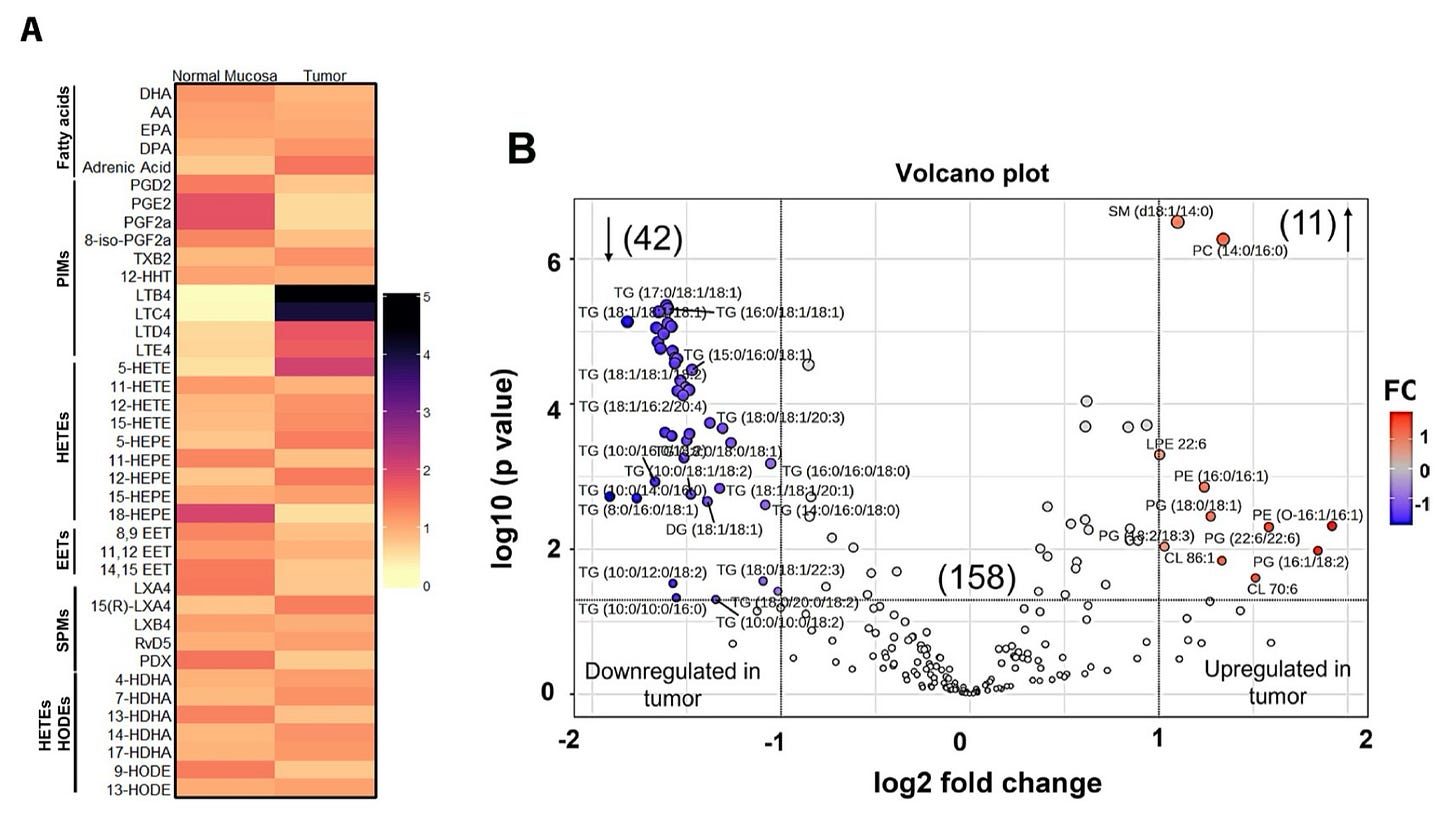

Key findings from the comparison of tumour and non-tumour biopsies:

Tumour cells and their surrounding tissue showed higher levels of certain inflammatory lipids (fats). This is where some people have implicated seed oils, as some of those lipids are derived from linoleic acid.

The tumour cells exhibited lower levels of compounds that reduce inflammation.

Tumour cells and nearby immune cells showed a dysregulation in the expression of genes related to lipid metabolism, preventing these cells from transitioning from an inflammatory state to an inflammation-resolving state.

These observations hint at unresolved inflammation in the tumour microenvironment, but this is not exactly groundbreaking news given that chronic inflammation is a known hallmark of cancer development.

The figures below, direct from Soundararajan et al.’s study, show a difference between the lipid profiles of tumour cells and normal cells. While we can hypothesise that these altered lipid profiles may have supported tumour growth and survival, these findings certainly don’t link linoleic acid consumption to colorectal cancer.

The media misstep

Here’s where it falls apart: finding inflammatory lipids in tumour cells doesn’t mean those lipids caused the cancer. The study’s authors never made that claim. And even if inflammatory lipids were indeed a culprit, they could have come from any dietary source of linoleic acid — including meat fats, eggs, soy, nuts, avocados, or processed foods. Crucially, Soundararajan et al. didn’t review the participants’ diets in any way.

Just a note here to say that Soundararajan et al.’s work is a solid exploratory investigation. The problem lies not with the research but with how it’s been misinterpreted and sensationalised in the media.

Journalists appear to have latched onto a hypothesis by Soundararajan et al. that Western diets — low in fibre and high in linoleic acid — might have contributed to the inflammation they observed in the tumour environments. However, this hypothesis needs to be weighed against all the evidence we’ve just looked at, which shows that moderate to high (but not excessive) linoleic acid intake is actually very good for us.

So are seed oils good or bad?

Seed oils have a rich nutritional profile. They’re a good source of omega-6 fats, which are essential for life, and are rich in vitamin E.

There has been much debate about linoleic acid, the main omega-6 fat found in seed oils. Because linoleic acid is linked to inflammation, some people worry that it might increase the risk of cancer and heart disease. Linoleic acid is an ‘essential fatty acid,’ meaning it is vital for life but can’t be synthesised by the body — it must be obtained through our diets.

Linoleic acid metabolises into arachidonic acid, which plays many critical roles in the body. It supports development, helps fight infections, and assists wound healing. Additionally, it’s a critical component of our cellular membranes, which provide structure to every single cell in the body.

A look at the evidence

With all the fuss around linoleic acid, researchers have been studying it for decades — there is no shortage of quality data. Here are some of the strongest studies:

1. Reduced death rates

Researchers in Finland followed 2,480 people for an average of 22 years. They took regular blood samples to measure levels of omega-6 fats, including linoleic acid and arachidonic acid. They also tracked deaths.5

The results show that:

Those with higher levels of linoleic acid were 43% less likely to die from any cause.

Those with higher levels of linoleic acid had a 46% lower risk of dying from heart disease.

Those with higher levels of linoleic acid had a 52% lower risk of dying from non-heart disease and non-cancer causes (e.g., respiratory diseases or infections).

Higher linoleic acid levels were not associated with cancer deaths, meaning they did not increase or decrease cancer mortality risk.

The protective effect of linoleic acid (against death) was similar whether or not participants had a history of chronic diseases like heart disease, cancer, or diabetes.

Takeaway: Higher levels of linoleic acid in the blood are associated with a lower risk of death. Importantly, the study found no evidence that higher omega-6 fat levels increase cancer-related deaths. Seed oils appear to be protective rather than harmful.

2. No change in inflammation

A meta-analysis of 30 different studies, involving 1,377 participants, analysed what happened to inflammation markers when people increased the amount of linoleic acid in their diets.6

The results show that eating more linoleic acid did not change levels of inflammatory markers in the body (including cytokines, TNF, IL-6, or adiponectin).

The one caveat was that, in some cases when people made an extreme increase in linoleic acid intake, there was a slight increase in CRP levels (an inflammatory marker in the bloodstream) — though this effect wasn’t consistent across studies.

Takeaway: Adding moderately more linoleic acid to your diet, such as from seed oils, doesn’t increase inflammatory markers. However, extreme increases in linoleic acid intake might have small effects on CRP in some people.

3. Reduced cardiovascular disease

Another large meta-analysis compiled 30 long-term studies conducted in 13 different countries. The analysis included 68,659 people who were followed for up to 32 years.7

Researchers looked at levels of linoleic acid in the blood and tissues, and compared this to rates of heart attack, stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes. They also checked whether factors like age, sex, diabetes, or use of medications affected the results.

The results show that people with higher levels of linoleic acid in their bodies had a 7% lower risk of cardiovascular disease and a 22% lower risk of death from cardiovascular events. Arachidonic acid was also found to lower the overall risk of cardiovascular events.

Takeaway: Eating foods rich in linoleic acid, like seed oils, may help prevent heart disease and lower death from cardiovascular causes.

4. Improved physical function

Researchers in the States analysed data from a group of older adults (average age of 74 years) who had participated in a larger study about ageing, health, and energy use. The participants’ diets had been tracked, and those eating a suboptimal amount of linoleic acid were classified as having "low LA intake."8

The results show that people with low linoleic acid intake were 2.5 times more likely to have trouble climbing stairs compared to those who consumed more linoleic acid. Results were adjusted to account for other factors that might affect physical ability, such as age, weight, and other health conditions.

Takeaway: Eating enough linoleic acid may help maintain physical function in older adults. Linoleic acid is essential for our cells to produce energy.

The case against seed oils

Alright, we get it — the linoleic acid in seed oils saves lives. So why has it stirred up so much debate?

Some research in animals has linked high linoleic acid intake to increased inflammation and tumour growth. For instance, studies have found that mice on diets rich in linoleic acid showed enhanced tumour growth.9

In laboratory cell-based studies, linoleic acid has shown pathways leading to inflammation. One example is a study of trophoblast cells, where exposure to linoleic acid led to an increase in prostaglandin, a pro-inflammatory mediator.10 However, large human studies (like those already discussed) have failed to confirm this.

A few human studies (discussed above) have suggested extreme linoleic acid intake could slightly raise CRP levels, an inflammatory marker. However, this effect is inconsistent across studies and minimal at best.

It’s important to remember that, while lab studies and animal models can raise theoretical concerns, they don’t always translate to real-world human outcomes. The overwhelming body of large-scale human research shows that linoleic acid is good for our health when consumed at normal to high (but not excessive) dietary levels.

High heat can make seed oils harmful

One thing to keep in mind when cooking tonight’s dinner is that harmful byproducts, known as reactive metabolites, can form when seed oils are heated to very high temperatures — such as during deep frying. Polyunsaturated fats (like those found in seed oils) are particularly prone to oxidation at high heat, leading to the production of toxins such as aldehydes and ketones. These can increase oxidative stress in the body, which may contribute to health issues over time.

However, it’s important to distinguish between different cooking methods. The general use of seed oils in everyday cooking — such as sautéing or baking at moderate temperatures — is unlikely to produce harmful byproducts. Proper storage and avoiding excessive reheating can further minimise the risk. When used appropriately, seed oils are a safe and nutritious part of a balanced diet.

The real culprit: Ultra-processed foods

If you’re looking for dietary villains, ultra-processed foods are the real culprits. These foods are typically low in fibre, high in refined carbohydrates, and loaded with salt, sugar, and – yes – seed oils. However, it’s the overall nutritional profile of these foods, not just the oils, that’s a problem. Overconsumption of ultra-processed foods has been linked to chronic inflammation, weight gain, and an increased risk of lifestyle-related diseases. Shifting to a balanced diet rich in whole, minimally processed foods is far more effective for health than fixating on the type of oil in your frying pan.

Takeaways for your kitchen

Should you ditch seed oils entirely? Not necessarily. Here are some practical tips to keep your meals healthy while avoiding the media scaremongering:

Incorporate a variety of oils, such as olive oil, avocado oil, and flaxseed oil, to diversify your fat sources – but don’t shy away from seed oils.

When you’re cooking at high temperatures, choose oils with high smoke points and stable fatty acid profiles, such as avocado oil or refined olive oil (extra virgin is less stable at high temperatures). Seeing smoke is a clear indicator that an oil is breaking down into harmful compounds.

Prioritise high-fibre foods to help reduce inflammation and support gut health. Think whole grains, beans, and leafy greens.

Limit ultra-processed foods. This simple step is one of the most effective ways to manage your intake of less-than-ideal ingredients, and prevent excessive seed oil consumption.

Seed oils aren’t the enemy. Misinformation is. The notion that seed oils are driving a colon cancer epidemic is a textbook case of oversimplification and media hype. While it’s wise to be mindful of your omega-6 intake, demonising a single ingredient without understanding the broader dietary context does more harm than good. So, go ahead and stir-fry those veggies. Your colon – and your common sense – will thank you.

Virtanen, J. K., Wu, J. H. Y., Voutilainen, S., Mursu, J. & Tuomainen, T.-P. Serum n–6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of death: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 107, 427–435 (2018).

Marklund, M. et al. Biomarkers of dietary omega-6 fatty acids and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality. Circulation 139, 2422–2436 (2019).

Su, H., Liu, R., Chang, M., Huang, J. & Wang, X. Dietary linoleic acid intake and blood inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food & Function 8, 3091–3103 (2017).

Soundararajan, R. et al. Integration of lipidomics with targeted, single cell, and spatial transcriptomics defines an unresolved pro-inflammatory state in colon cancer. Gut gutjnl-332535 (2024).

Virtanen, J. K., Wu, J. H. Y., Voutilainen, S., Mursu, J. & Tuomainen, T.-P. Serum n–6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of death: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 107, 427–435 (2018).

Su, H., Liu, R., Chang, M., Huang, J. & Wang, X. Dietary linoleic acid intake and blood inflammatory markers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food & Function 8, 3091–3103 (2017).

Marklund, M. et al. Biomarkers of dietary omega-6 fatty acids and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality. Circulation 139, 2422–2436 (2019).

Belury, M. A., Clark, B. C., McGrath, R. & Cawthon, P. M. Linoleic Acid Intake and Physical Function: Pilot Results from the Health ABC Energy Expenditure Sub-Study. Advances in Geriatric Medicine and Research (2022).

Jin, R. et al. Dietary fats high in linoleic acids impair antitumor T-cell responses by inducing E-FABP–Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Cancer Research 81, 5296–5310 (2021).

Shrestha, N. et al. Linoleic acid increases prostaglandin E2 release and reduces mitochondrial respiration and cell viability in human Trophoblast-Like cells. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 52, 94–108 (2019).